Throughout much of 2022, I poured over art books, especially featuring women artists who create abstract work: Georgia O’Keefe, Helen Frankenthaler, Elaine de Kooning, Sonia Delaunay, Judi Chicago, Mary Cassatt, and Hilma af Klint.

An aside: Do you know the name Lee Krasner? Probably not. She married Jackson Pollock in 1942 and he was her pupil. But why is Pollock the name we all know and not Krasner? I wonder.

What is abstract art? It’s not a style or genre, but a mode or method, says one male abstract artist and historian. Another male artist says it is a form of language based on visual symbols.

For years, abstract painters who became famous and got all the exhibitions in museums have been disproportionately male. We barely know all the names of the women who pioneered abstract art and basically provided a road map for the men to follow: Who is truly an abstract painter? The names we now recognize easily or the names we still don’t know?

A book I got from the library has filled the gaps in my knowledge, WOMEN IN ABSTRACTION, and what a wondrous delight is it to see the history of abstract painting stretching back as far as the 1880s. Georgina Houghton birthed the movement, art that at its inception was assumed grew from spiritualism roots. These days, abstract art’s chronology is continuously being rewritten and has little to do with spiritualism; it’s everywhere in our modern lives and is often now what makes a space feel truly modern. Look at West Elm or Marimekko for a glimpse of abstract art that lives in our homes with us. It says nothing about our souls, but it does give our souls peace, at least it does mine.

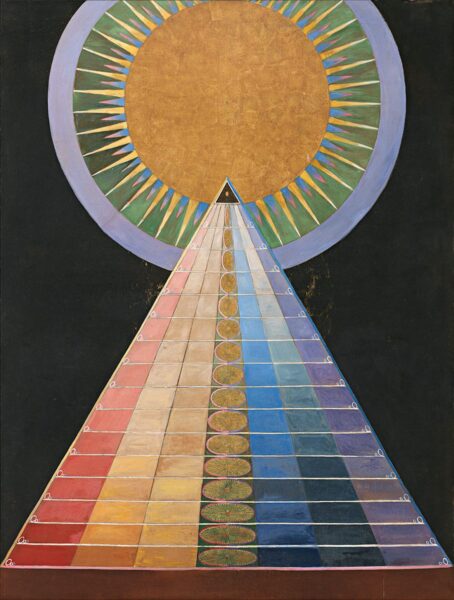

In the past few years, I’ve been obsessed with and collecting books about Sonia Delaunay, a 1930s-era French abstract painter (also a fellow surface pattern designer and quite famous in her native country), but in 2021, I fell in love with Hilma af Klint. Not because of her mysticism and obsession with spiritualism, but because her art is incredibly cool.

For my holiday gifts this year, I received several books about Hilma af Klint’s work. (Note: If you love horror shows on streaming services, ARCHIVE 81, based on the podcast by the same name, has a character and plot line loosely based on af Klint’s life/work, and no, af Klint’s real life and real contribution to art were not horrifying in the least, contrary to the show. It’s a great show, if you like gory horror and want to be scared, though. I’m bummed we won’t get a second season.

I seek to enjoy af Klint’s work through the abstract lens, cutting away her Madame Blavatsky mysticism and long and committed venture into spiritualism. She’s got a great eye, and her work, locked away by her heirs for twenty years after her death at her request, has not been widely shown until the 2010s. But recently several books have been produced to introduce readers to not only her life, her interest in mysticism/spiritualism, and her working notebooks.

Hilma af Klint created luscious landscapes of her native Sweden in her earliest days of art making and it was these landscapes that she showed publicly through her life, and which provided her income. It was around 1880 that she began to explore the Theosophy of Madame Blavatsky after the death of a beloved sister and as she moved further into spiritualism, af Klint believed she heard from her “High Master” about the art she became dedicated to creating for the rest of her life. The Five were women artists who created automatic art at the bequest of these High Masters. They were creating art for a future world, a future religion, a future temple, one that they would not live to see, and one that they felt sure the world needed to survive the future.

Of course, nothing of the sort came to pass. The spiritualism of the early twentieth century was quickly replaced by other beliefs as the world changed, and more wickedly, the abstract art of men was given higher billing. In 1934, artist and patron Katherine S. Dreier, who in 1920 had co-founded the Societe Anonyme, Inc., the first musuem of modern art in the United States, with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, put on a show of female-only painters called “From Impressionism to Abstractionism.” And Peggy Guggenheim hosted female abstract painters in her gallery in the 1940s.

As WOMEN IN ABSTRACTION reports: “Although they were known in their day, none of these artists have been accepted into the ‘canon,’ proving, if proof were needed, how much the narrative has sidelined important figures, and raising questions about a system of art history that could marginalize certain works.”

It wasn’t until the 1970s that female abstract artists were again given exhibitions and shows. And during this decade, Hilma af Klint still waited. It was not until 1984 that Hilma af Klint’s work was shown to an audience. Over 1200 pieces of art! It was not until 1986 when her work was shown in Los Angeles at an exhibition that af Klint received international attention. And now, nearly forty years later, we’re getting books and even a movie (available on Kanopy). In spring 2022, af Klint’s exhibition in Wellington, New Zealand drew thousands of visitors.

Perhaps af Klint was creating art for the future, just not in the way she thought. Rather than for a temple dedicated to a “High Master,” instead we get to experience Hilma’s vision knowing that humans are fallible and that perhaps art, in which we recognize the humanness of the work (not the AI-created mishmash failures now being produced by software) we now get to see the incredible imagination of an artist whose work was and will remain timeless.

Hilma af Klint, Paintings for the Temple, 1915 (source: Guggenheim).

Very insightful!